Have you ever opened a fly box and was overwhelmed by the different shapes and patterns of flies? Some of the most common questions I have received are, “Will this fly be fished subsurface or on the surface?”, “What does this fly mimic?”, “How do I know what fly to use?”.

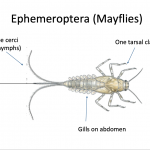

To adequately answer these questions, I need to start by explaining the life cycle of an aquatic insect and the behaviors of the insect during each cycle. Here, I will explain the life cycle of a mayfly as a proxy of the general aquatic insect life cycle and discuss tips on how to match flies to the certain life cycle stages. Of course there are more aquatic insects that are used in fly fishing, like caddisflies, stoneflies, and midges that have slightly different life cycles, but we will focus on mayflies first, as they are the most primitive of aquatic insects…